-

Ngā Karere me Ngā Rauemi

News and Resources

Ngā Karere me Ngā Rauemi

News and Resources

-

Te Rangaihi Reo Māori

The Movement

Te Rangaihi Reo Māori

The Movement

-

Te Pae Kōrero

Our Community

Te Pae Kōrero

Our Community

-

Huihuinga

Events

Huihuinga

Events

-

Ngā Ara Ako

Learning Pathways

Ngā Ara Ako

Learning Pathways

-

SearchSearch

Search

Search

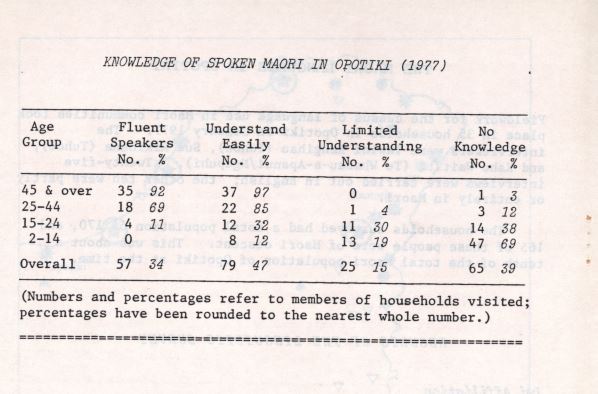

Many people were worried not only that fewer and fewer people could speak Maori, but also that the language may not last much longer. There was a lot of support for teaching Māori in schools, especially at the primary level, but some people said that the language had to be learned and spoken in the home first. They also said that Maori had to be helped along in the community as a language for everyday use, and not just a classroom subject or a language mainly for ceremonies on the marae. People said that there had to be more and better Maori language and culture programmes on TV and radio. More and more people, from school children to grown ups, are learning the language in schools, on marae or in private homes. All the same, some people in Opotiki gave Maori little chance of staying alive in towns and cities where English was always the main language for everyday use. They only spoke Maori in their country home areas, and used English with their neighbours friends or workmates in Opotiki.

Source: Read the full NZCER report here

Te Moana-ā-Toi | Bay of Plenty | Ōpōtiki | 1970-79 | 5% of Māori children can speak te reo. (1970-75) | Story is by tangata whenua

Comments