-

Ngā Karere me Ngā Rauemi

News and Resources

Ngā Karere me Ngā Rauemi

News and Resources

-

Te Rangaihi Reo Māori

The Movement

Te Rangaihi Reo Māori

The Movement

-

Te Pae Kōrero

Our Community

Te Pae Kōrero

Our Community

-

Huihuinga

Events

Huihuinga

Events

-

Ngā Ara Ako

Learning Pathways

Ngā Ara Ako

Learning Pathways

-

SearchSearch

Search

Search

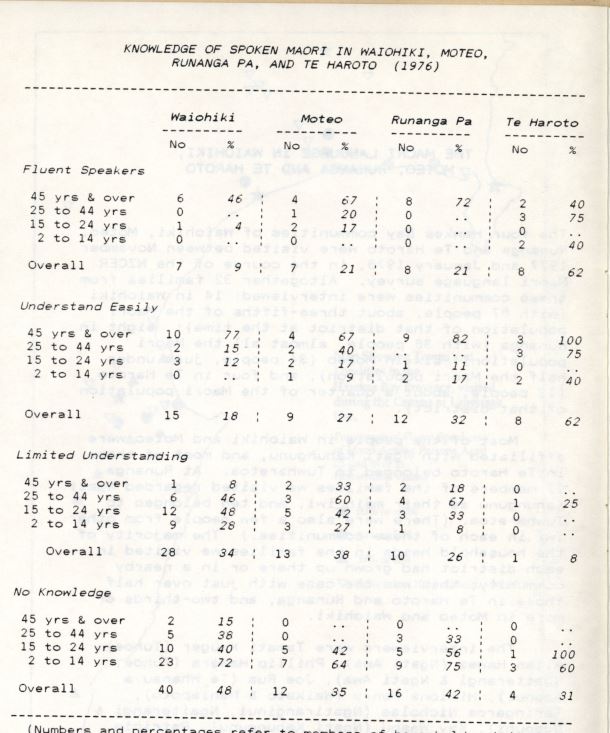

A man in Mateo told us that he had been punished for speaking Maori at school, and the loss of confidence he felt then had lasted, so that he does not speak on the marae even though he ought to be one of the people to do so. A woman in Waiohiki also attributed her loss of fluency in Maori to her experiences at school. Families also had a part to play in forming attitudes to Maori, of course. Another person from Waiohiki told us that her parents supported the school's disapproval of Maori by using only English with the children, trying to help her get a good education. There is no doubt that, in the past, many teachers sincerely believed that the use of the Maori language was a major obstacle to progress and economic advancement for Maori people, and it is not surprising that many parents, concerned that their children should have a better chance in life, came to accept this view. By the time of the survey, many people had come to feel that the exclusion of Maori from school and home had been unfortunate, and that they and their children had lost something very precious because of this. So there was considerable support for the revival of the language, including its use in schools.

Te Matau-a-Māui | Hawke’s Bay | Hastings | 1970-79 | 5% of Māori children can speak te reo. (1970-75) | Story is by tangata whenua

Comments